Almost time for Passover dinner and the assembled guests are shifting their interests from songs to soup. At the apex of the Seder, we point to the Passover symbols and begin our meal with horseradish and haroset. It is also the moment when we balance the existential bitterness with the perception of sweetness.

According to the Talmud (tractate Pesachim daf 116), explanation of the Passover symbols is among a very few essential elements of a Seder. These explanations are offered just before blessings over the food. They are the symbols of a lamb sacrificed, the bread of affliction and a taste of bitterness.

Bitterness emanates from the realm of emotion. Bitterness is developed in how we react to adverse events, often beyond our control. When we despair, when we lose hope, when we are weak in our faith, bitterness metastasizes.

One lesson gleaned from the Seder is that bitterness can be tempered with an appreciation of what is sweet. We remember enslavement by pointing to the maror but we eat the bitter herbs together with some honeyed haroset. We redeem ourselves when we control our bitterness with a balance of sweetness. And the sweetness is delivered in a symbol of oppression, the concoction of nuts and apples that reminds us of the mortar used to build Pharaoh’s storehouses. Haroset invites us, in the grips of adversity, to seek some sweetness – knowing that for our enslaved ancestors, sweetness must have been very, very hard to find

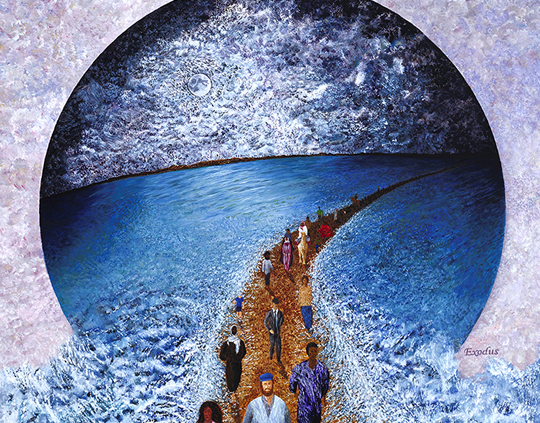

A challenge of Passover is finding balance to the adversities in our lives; ranging from the daily routine to the great challenges of life and death, love and loss that touch everyone at one time or another. Our task is to identify and try to connect with what is also sweet in our lives perhaps with appreciation for our blessings. The process culminates on the seventh day of Passover with a celebration of crossing the sea in the final steps away from Egyptian oppression. How can we facilitate the transition from bitterness to sweetness? When we permit ourselves faith in possibilities of a better life and improved world in which we live. Both the physical journey to the Sinai and the psychological trek from bitterness to blessings takes courage and determination. The result is a legacy of hope that we pass down from generation to generation, – a hope that our tradition remains vital and continues giving us the chance for an ever more meaningful and joy-filled life.

R Evan Krame

(Join us Friday night April 29 at 6:30 for a sweet musical and mystical last day of Passover and welcoming of Shabbat at the Women’s Club of Bethesda – www.thejewishstudio.org/our-calendar).

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the