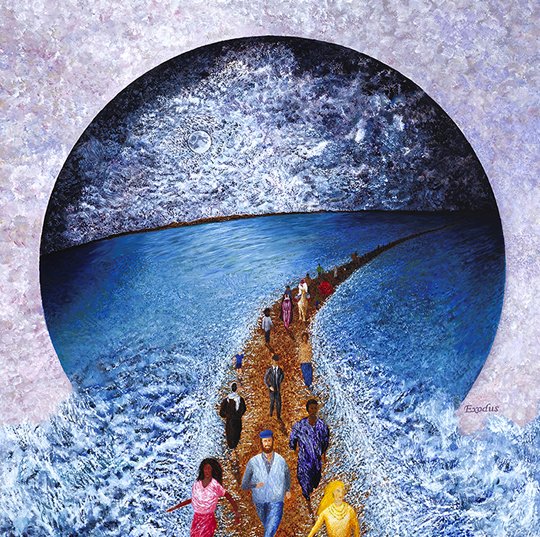

It’s time for spring cleaning, a lead-up to Passover’s journeying of renewal and liberation from narrow places. Bounding beyond the narrow (tzar) troubles (tzarot) of bondage in “Egypt” (Mitzrayim) toward freedom anew maps to this week’s similarly-named Torah portion (Metzora) journeying from illness and isolation toward health and restoration. In this journey from Egypt (Mitzrayim) and this illness (Metzora), the message is going forward: means may be unclear and readiness may falter, but the time absolutely and urgently is now.

To understand this pre-Passover message, we enter deeply into the eerie ancient world of tzora’at, the Hebrew word (notice the same Hebrew root, tz-r) for this illness. Tradition imagines tzora’at as leprosy, except houses also got tzora’at (Lev. 14:34). We know only that tzora’at was a spiritual sickness affecting both people and buildings, and whose symptom was surface eruptions (from skin or walls). In either case, the remedy was temporary isolation and then a complex purification ritual.

Some ancient rabbis reasoned that anyone ill deserved it for some spiritual reason (B.T. Berakhot 5b). Explanations abounded: some said that tzora’at visited the slanderer, with skin eruptions bringing outside the condition of one’s inside. Maybe tzora’at afflicted the arrogant, symbolized by the lowly hyssop bush used for cure (Lev. 14:4). Others imagined tzora’at plaguing the stingy, emptying the afflicted’s house so all could see hoarded wealth withheld from charity (Lev. Rabbah 17:2). All we know for sure is that these explanations share a common sense of inner narrowness.

Against that backdrop, given the Jewish premium on community, the tzora’at cure of isolation – being placed outside the camp – was important and symbolic. Rabbi Shefa Gold teaches that the cure for narrowness was then – and remains today – a spiritual time-out and separation from routine and community. In modern forms it might be a retreat, going out and away from routine. In psychological terms it might be a temporary ejection to re-set emotional and psychosocial circuits. Whatever the form, the message is much the same: when narrowness comes, you can’t stay where you are. And a second message follows the first: the response to seeming external affliction (skin eruptions) focused internally. Appearance might be skin deep, but perception and reality root deep within: it’s at this level that our search for healing and renewal must most focus.

So too with Passover. When it was time to go, there was no readiness: had our ancestors waited until they felt ready, they might never have left! And so too with Passover’s rituals: the outer rituals of home preparation, eating matzah and conducting a seder seek not outer performance but inner change, to identify inwardly with the fleeing slaves: “I do this because of what God did for me when I came out of Egypt” (Ex. 13:8).

So whether it’s inner bondage or outward appearance, how we speak or what we give, where we live or where we travel, this moment readies us to journey past every sense of narrowness and inner sickness we can fathom, trusting that separation from community or routine might be necessary to recalibrate us for the journey ahead. Get ready, knowing that there’s no real ready. Get set, knowing that set is besides the point. Just go.