Have you been to a poetry slam? It’s a form of poetry competition. The poets present their works in a struggle for dominance. One doesn’t naturally associate poetry with a sport. Drop any notion of poetry as a lovely art form. The poems presented are often confrontational and clever. There is no chance Elizabeth Barrett Browning would win one of these. Yet it begs the question, what is the role of poetry that is confrontational?

In the Torah reading for this week Moses says: “Write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths, in order that this poem may be My witness against the people of Israel.” A poem stands as witness, like an accuser in a courtroom. Like Picasso’s masterwork Guernica, a grey toned depiction of the Spanish Civil War’s destructive aftermath, Moses’ poetry calls to the conscience of each person who might have been tempted toward immorality.

The Greek historian Polybius wrote: “There is no witness so dreadful, no accuser so terrible as the conscience that dwells in the heart of every man.” Polybius could have been talking about the High Holidays, when the liturgy beckons us to use our own thoughts to stand as witness to our shortcomings in this process we call teshuvah. It is not easy to set aside the ego and the protective instinct that insulates us from doing the soul work necessary to improve ourselves. At Proverbs 18:17 we learn that the one who pleads his cause first seems righteous but his neighbor will come and expose him. For me, this means that we need accusers, like Moses’ poem, to expose us to our own failings and set us on a path of improvement.

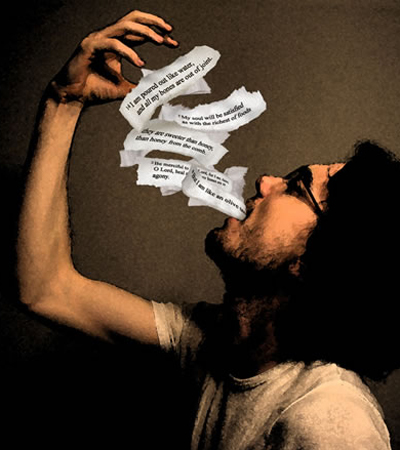

In the special way that a painting or poem can unlock the heart, we should also have prayers and services that help open us up to our errors and shortcomings during these High Holidays. That is one role of the liturgy and of clergy. Our job is to employ words to their purpose of urging us on toward self-improvement. The words can be prayer or poetry. My prayer for these yamim noraim, these Days of Awe, is that the machzor prayer book, like Moses at a poetry slam, stands as witness and confronts you so that your heart is open to do meaningful teshuvah.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame