Act Three

If there is a gun in act one, there had better be someone getting shot in act two. And if there’s unexpected gifts of jewelry in act one, there’s going to be a golden calf in act two. Just wait until Act three!

In Torah, after nine deadly plagues, Moses receives God’s instruction to have the Israelites “borrow” gold and finery from the Egyptians. Here’s the text (Exodus 11:2): “Tell the people to borrow, each man from his neighbor and each woman from hers, objects of silver and gold.”

The Egyptians are on the ropes. They endured plagues that denuded the land and faced starvation. Then the Hebrews came a-knocking, asking may I have your jewelry (as they might be borrowing a cup of sugar)? The Hebrew God has destroyed Egypt. How would we expect them to answer? The text suggests another divine intervention in the next verse.

“The LORD disposed the Egyptians favorably toward the people. Moreover, Moses himself was much esteemed in the land of Egypt, among Pharaoh’s courtiers and among the people.” God had the power to both end slavery and convince the masters to provide parting gifts.

With good feelings for Moses in their hearts, the Egyptians gladly lent their finery to his people. There is no mention in the text of any sort of loan document, bailment, or date of return, because, as we know, the jewelry won’t ever be returned. Some commentators opine that the jewelry received was not borrowed but rather paid in recompense for enslavement.

At Sinai, in Act Two, that same jewelry was melted to form a golden calf. This is the most shameful episode in Torah. The people lost faith and debauchery ensued.

Then came Act Three. The Israelites brought contributions to build the mishkan. Unlike the disgraceful golden calf, the mishkan was a place for God’s presence to be manifest on earth. The Egyptian finery was sufficient to make an idolatrous calf with enough left over to decorate the mishkan.

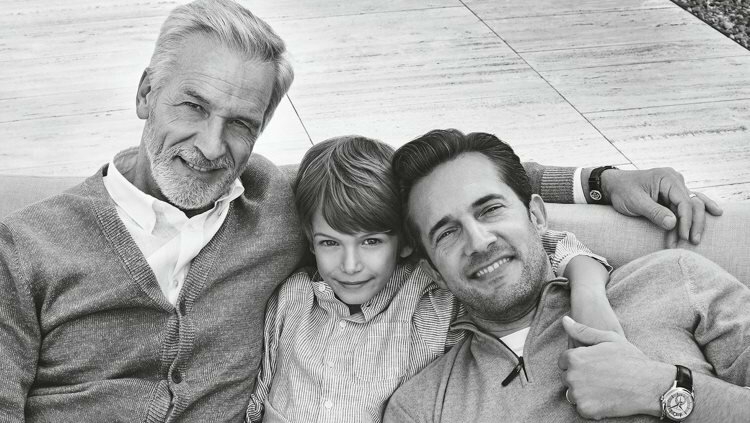

This play has many more acts, some canonized and others yet to be written. It begs us to consider what will we do with the treasures of the past? We might learn from the marketing for Patek Phillipe watches. “You never actually own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation.”

Our society is far too attached to possessions. I know this because my millenial children tell me so; a fact I remembered while admiring the new Tiffany’s store in town. Absent a gun pointed at our heads, we hold tight to jewelry, wallets and most especially our iPhones. Torah not only encourages us to share our wealth, but to do so with holy intention.

Do we form unholy attachments to possessions and worship our chattel? What motivates us to part with these borrowed valuables? Is it guilt, like the motivation for making reparations? Is it faithlessness that compels us to create idols? Or is it to welcome the Divine presence?

Our finest possessions are just borrowed for a short while. Ownership is transitory. Giving is transformative. The next act of the Jewish people is dependent upon how we share what is borrowed from the past to create a better future. When sharing our wealth, let’s ask, are we paying for golden calves or building modern mishkans?

R’ Evan J. Krame

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the