A Separate Peace

Can brothers who have been in conflict bridge the divide between them? Torah offers a lesson on how to quell rivalries and disguise plans to achieve a separate peace. What the story doesn’t include is how to evaluate the real opportunities for reconciliation.

Brothers Jacob and Esau are reunited in Parshat Vayishlach וישלח more than two decades after Jacob wrangled for the family birthright and then fled from Esau’s wrath. Jacob returned to Canaan with his wives and children. Yet, Jacob feared a reunion with Esau, a man inclined toward violence now surrounded by a powerful coterie.

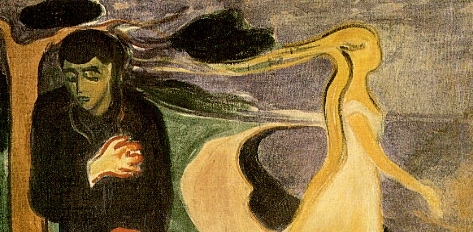

On the way, Jacob encountered an angel with whom he struggled all night long. In so doing, Jacob acquired a new name, Israel, meaning one who struggles with God. Angel wrestling posited as a tangible struggle might be the spiritual climax of the story. But a fateful and poignant internal struggle within Jacob was yet to be resolved.

The story sets out a schematic of how to act when confronted with someone we distrust. Jacob engaged Esau through bribery, flattery and excuses. As Jacob approached Esau’s camp, he sent gifts ahead to appease his brother. Upon reuniting, Jacob flattered his brother saying that seeing Esau is like seeing the face of God!

If Esau was still hostile to Jacob, that negative emotion was sheathed. Esau greeted Jacob tearfully, hugging and kissing Jacob and welcoming him back. Esau even offered to share his land with Jacob. In reply, Jacob remained diffident and offered excuses to avoid accompanying Esau, careful not to be offensive.

Jacob must have been confused by Esau’s effusively warm greeting. Earlier threats to Jacob’s life were not addressed and have not been forgotten. And there was no apparent recourse for resolving their prior conflict.

After this reunion, Jacob enters an internal struggle on how best to reboot a relationship with a brother he still does not trust. Jacob’s resolve is to keep the peace first by appeasement followed by separation. Neither Jacob nor Esau pursues teshuvah, a turning of their hearts with regret, recompense and resolve to self-improvement. Perhaps neither man was capable of atonement.

The tradition has been to demonize Esau not allowing for the possibility that he has changed. Perhaps Jacob is also flawed. Jacob wasn’t an angel – he just wrestled them. Jacob might not have had the capacity to be transparent and to be accountable for his own misdeeds. By failing to engage in a process of teshuvah both brothers demonstrate that neither is prepared for a real reconciliation.

There are two reasons I can offer as to why there was no true reconciliation between these brothers. First, as flawed humans, some adversaries are ill-equipped to be decent or well-mannered such that the better resolution is appeasement and separation. Taken a step further, Teshuvah is not always a viable option for every person – there are psychological impediments we must acknowledge.

The second reason why reconciliation may not have happened is our inclination toward reactivity to past events. In this case, it may have been that reconciliation was not possible because of lingering doubts and persistent mistrust. In the long shadow of Esau’s bellicosity, Jacob chose protection as a first course of action. Restraint engendered by fear is a legitimate choice even as we might desire reunion.

There are times when caution may be preferred to collaboration and even guile is acceptable in pursuit of peace. The trick is figuring out when reconciliation is not possible, and the need for separation outweighs the possible benefits of cooperative coexistence. By merely posing this scenario, Torah offers that not every dispute will be resolved but, at a minimum, steps to avoid violence are always obligatory.

In life we sometimes must struggle with opponents who have competing values and aggressive natures. The best we can do is to integrate Godly values into our thinking, like preventing violence, pursuing justice, and practicing teshuvah. The search for the right path might be to require us to balance laudable goals of protection and tranquility with difficult processes of engagement and reconciliation.

I wish I had more guidance to offer and that this Torah portion posed definitive ways to resolve conflicts. For myself, the dissonance between protection and longing for reconnection is a painful place to remain. Ultimately, we are each left to choose how to navigate contentious relationships from among psycho-spiritual maps of emotional struggles and competing values. But there seems no chance for actual reconciliation without a process that begins with our own willingness to be transparent and account for our own mistakes.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the