On the twenty-first new sun of March,

After the men and women had first gone forth,

Walking arm in arm

Ministers, Priests, and Rabbis

Young people and old

Finally marched over the Edmund Pettus Bridge,

From Bloody Sunday until that day

The people were going forth from the city of Selma in the land of Alabama

To the capitol steps in Montgomery

To pray with their feet that Congress pass a Voting Rights Act.

And the nation stood before a new land,

A land of rights restored.

Yet the people saw new plagues

Of evil resistance, rampage, and terror.

And all the people encamped

In the wilderness of not knowing.

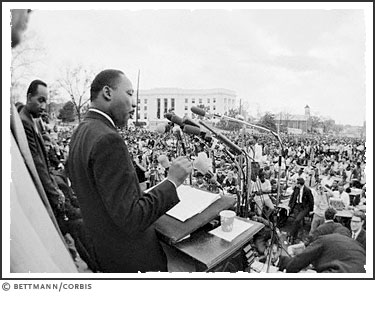

Then Martin went up

And at the top of the steps,

As God had called to him,

So he called to them, saying,

“I know you are asking today, ‘How long will it take?’

Somebody’s asking, ‘How long will prejudice blind the visions of men?’…

I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because truth crushed to earth will rise again.

How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever.

How long? Not long, because you shall reap what you sow.

How long? Not long.

Truth forever on the scaffold,

Wrong forever on the throne,

Yet that scaffold sways the future,

And, behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow,

Keeping watch above his own.

How long? Not long,

Because the arc of the moral universe is long,

but it bends toward justice.

How long? Not long, because

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He has loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on.

These are the words that you shall speak to the children of America.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame

one of the last surviving remnants of a historic Black community that once included a church, a school, and several dozen homes. The Moses cemetery hosts about 500 graves of former slaves and sharecroppers. Many were displaced from homes in the District of Columbia and pushed into adjoining farmlands in Maryland, along River Road. Montgomery county now owns this land. The Housing Opportunities Commission is selling the land to a private developer. The Bethesda African Cemetery coalition sued the County to protect the Moses Cemetery development.

one of the last surviving remnants of a historic Black community that once included a church, a school, and several dozen homes. The Moses cemetery hosts about 500 graves of former slaves and sharecroppers. Many were displaced from homes in the District of Columbia and pushed into adjoining farmlands in Maryland, along River Road. Montgomery county now owns this land. The Housing Opportunities Commission is selling the land to a private developer. The Bethesda African Cemetery coalition sued the County to protect the Moses Cemetery development.

e wisdom about friendships.

e wisdom about friendships.

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the