Fashion Fit for the Soul

Clothing does not merely make a fashion statement. Nowadays, consumers are more likely to purchase clothes that best enhance experiences, like yoga pants. Moreover, we are approaching a time when clothing is less about standards of style and more about realizing the identity of the person. The new approach to garments may challenge the clothing norms established by religious tradition.

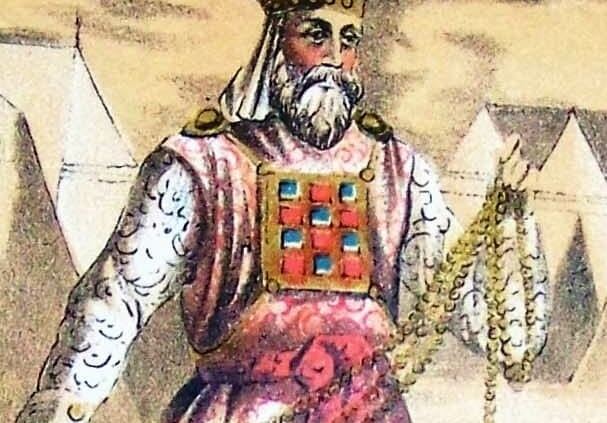

The Torah portion for this week, Parshat Tetzaveh, lays out instructions for the garments to be worn by the priests when offering sacrifices to God. The priestly robes are adorned with bells and pomegranates, blue thread and gold trim. Worn over those garments is a breastplate to which precious stones are affixed. The Priest’s costume was reserved for special sacrificial occasions.

If a man were to wear such clothing today, some might question their sartorial choices. By today’s standards, the priestly garb might be perceived on the feminine end of the clothing spectrum. This calls to mind Deuteronomy 22:5, “A woman must not put on man’s apparel, nor shall a man wear woman’s clothing; for whoever does these things is abhorrent to the LORD your God.” Yet, the priestly robes were not about gender but rather about bringing about a sense of awe and wonder.

No one expects the Rabbi or Cantor today to ascend the bimah in a decorated robe. The garb of those who fill priestly functions these days would likely be the tailored suit, whether the Kol Bo is a man or woman!

The “rules” that govern what men and women should wear are actually fairly arbitrary. We know that because they keep changing. In her book Cut My Cote, author Dorothy Burnham reports that clothing was initially based on the shapes of the animal skins or fabrics it was fashioned from. In fact, men and women in Europe and other cultures wore more or less the same garments for centuries.

Eventually clothing became more sophisticated and gendered. Yet, the standards of gender identification through clothing were ever changing. For example, in the early 20th century, the colors that delineated gender among children were the reverse of our expectation. Society considered pink the more suitable shade for boys, and blue was better for little girls.

The differences in the way men and women dressed in the 20th Century symbolized the supposed differences in the sexes: Men, like a suit, were to be serious and practical; women, like a flouncy dress, were to be frivolous and superficial. Clothing choices today better reflect social norms and gender identity.

With the rise of feminism, gay rights and other human rights movements, a push for genderless dressing has arisen. Genderless dressing doesn’t erase gender identity from clothing. It just loosens the constraints on what people should or shouldn’t wear.

Oft stated these days is the mantra “clothing has no gender.” NPD, a fashion industry consulting firm, reported, “Half of [millennials] believe gender exists on a spectrum and shouldn’t be limited to male and female. So retailers and manufacturers with their eyes on this most valued of consumer demographics started thinking of shoppers as more complex and varied. They’re more than just male or female.”

Change has begun. The world’s first gender free clothing store, the Phluid Project, opened in downtown Manhattan in 2018. Department stores across Europe have gender-neutral floors or departments.

We still live in a gendered society. But in the context of the history of clothing, how can we understand a commandment for dressing according to gender? Perhaps Torah’s intention is to state that we not dress to deceive, neither the world nor ourselves, with clothing inappropriate to our identity.

The questions being asked about garments today are “does the person feel comfortable?” and “does the person feel natural in their clothing?” I’d add this question, “by selecting clothing to honor individual identity, do we also honor God?” A religion that sees each person as created in the divine image should support those whose clothing choices reflect their God-given identity.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame (for my friend and teacher Rabbi Mike Moskowitz)

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the