A recent exhibit at The Brooklyn Museum reminded me of the potent spiritual power in building things, and how powerful the details can be – like color.

The featured exhibit was Infinite Blue and included diverse works of art – ancient Egyptian blue pottery, a 13th century altarpiece of Madonna draped in blue, and contemporary glass sculpture. Each work of art demonstrated how the color blue can evoke a spiritual and powerful response.

Perhaps this is why blue is significant in Jewish tradition. Blue was Creation’s first color: Creation’s first day was just light, but Creation’s second day brought sky and sea, both shining blue. Blue was God’s first building block.

Blue treads through Jewish spiritual life. Blue is the color of the thread (t’chelet tzitzit) in the prayer shawl (tallit). Gazing on the blue thread reminds us to connect with Creation and Creator: the blue dye is an aide-mémoire of the bond between the Jewish people and the Holy One.

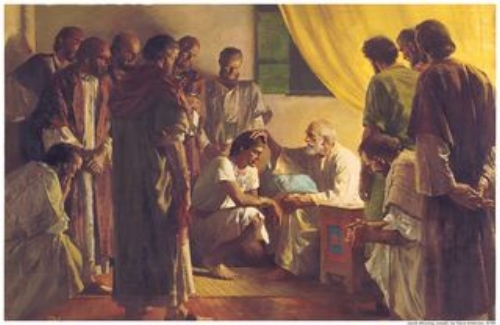

Blue’s most beguiling reference comes in Parshat Mishpatim, just after the Ten Commandments of Sinai. Moses, Aaron, Aaron’s sons and 70 elders ascend the holy mountain. There “they saw the God of Israel: under [God’s] feet there was the likeness of a sapphire brickwork (livnat ha-sapir), like the essence of sky in purity” (Exodus 24:10).

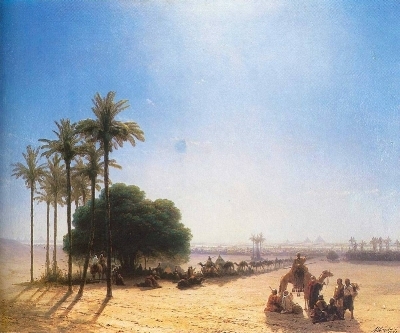

The “brickwork” links back to the Exodus story, with Hebrew slaves stooped in mud pits making bricks to build storehouses for Pharaoh. Mystics tell us that their muddy bondage was the 49th level of descent, just one level up from being forever lost. From this low place, their cries drew God’s attention and ultimate liberation.

Ten plagues, three months and twenty-four chapters later, Israel’s leaders now stand in God’s presence. Beneath God’s “feet” is blue sapphire brickwork. Pharaoh’s bricks became God’s bricks: mud became light. All at once, the image reminds them of the depths from which they came and the spiritual heights to which they have risen.

The sapphire brickwork is rigid and fixed in place. It serves as a liminal boundary, a separation. Yet the sapphire brickwork (livnat ha-sapir) also is translucent, letting in divine light filtered through to us as if through a prism. In Hebrew, we can readlivnat ha-sapir as l’vanat ha-sapir – the whiteness of the sapphire. The blue of spiritual building transmits the white light of holiness.

Every activity in this physical universe potentially refracts this divine light. When living our lives in divine service, we can achieve a satisfaction and pleasure we cannot achieve by our own self-serving efforts.

It was on Sinai that Moses and his cohort gazed on God’s likeness, reminding us also that many find spiritual connection in nature, whether viewing the sky from a mountaintop or watching waves reach the seashore. The challenge is to find spiritual connection in the works of our hands beyond the vistas of mountains, sea and sky. Torah’s vision of sapphire brickwork urges us to find connection beyond God’s original creations. Livnat HaSapir reminds us to discover our own transcendent connections in how we fashion Creation’s elements.

Whether our spiritual structures are sapphire stone, wood, metal or brick, every structure can serve – must serve – to remind us of the Source of All, the First Builder, and ancient bricks of mud transformed into bricks of light.

Rabbi Evan Krame

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the