Part of a yearlong series on resilience in spiritual life.

Meet a 99-year-old gentleman who yesterday circumcised himself and today runs a fever. Age and Infirmity aside, he runs to greet surprise guests at his door, then rushes to help his wife feed them. Missing an ingredient in the kitchen, he keeps running – first to get food, then to coordinate preparations.

What stamina and commitment! Who is this guy, and what special juice powers him up?

Meet Abraham, resilience superstar and rushing champ of this week’s Torah portion (Vayera).

Tradition acclaims Vayera for Abraham bargaining with God over Sodom and Gomorrah, the ruin of those cities, the unlikely birth of Abraham’s sons Ishmael and Isaac, the banishment of Hagar and Ishmael, and the binding of Isaac. Often unnoticed is Abraham’s heed of speed. Seeing his visitors, he “ran to greet them” (Gen. 18:2), from which Torah derives the mitzvah of welcoming guests. He then “rushed” to his wife, Sarah, and told her to “hurry” in preparing food (Gen. 18:6). Then he “ran” to his herd for calf and “hurried” his servant to prepare it (Gen. 18:7).

Why the rush? A traditional explanation for Abraham’s hurry is to show that one should strive to host guests with alacrity, joyful welcome and uninhibited generosity. We can ask a more basic question: how did a 99-year-old guy run around one day after circumcising himself?

Put another way, what gave Abraham resilience?

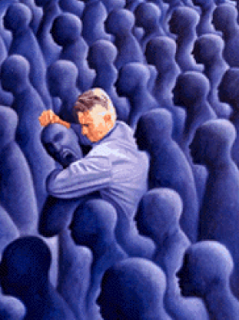

To me, two answers arise that really are one answer. Either Abraham transcended his pain because cared so much about his guests, or he transcended his pain because he sensed he was doing God’s will. Either way, the fount of Abraham’s resilience was that he cared about something more than himself. Tradition links Abraham with chesed (loving kindness) partly for this reason – his loving care that transcended himself.

As for Abraham, so for us. Love is our resilience updraft. When we care about another (or a cause, or a community) more than ourselves, we naturally boost our inner capacity to do, be and become. By lovingly serving something greater than ourselves, our love boosts our resilience.

Just ask our resilient rushing champ, Abraham.

– Rabbi David Evan Markus

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the