Yom Kippur teaches us the process of teshuvah. One element of our repentance is reconciliation. More than making amends for past wrongs, reconciliation demands education, understanding, and caring in the formation of a relationship based upon shared values. In 5782, I began a journey of discovering how we need reconciliation on a national level and how we Jews are uniquely qualified to lead the way.

I had not attended an in-person conference in the two years since the beginning of 2020. When I heard that Reconstructing Judaism would be meeting in a hotel in Northern Virginia, I registered. While I am not affiliated with that branch of Judaism, I hope to see friends who would be attending.

In an entrance foyer of the conference center at the hotel stood a large display. On the boards were the details of a resolution and supporting facts, graphs, and pictures. The resolution was a key program for the group. They called for reparations to be paid to African Americans.

I was confused. In my mind, this was a “Jewish conference.” While I might agree or disagree with the statement on reparations, I wanted to be inspired by some Yiddishkeit, some Torah, something Jewish. Moreover, I had not yet come to an educated understanding of the issue of reparations in America.

I was supportive of reparations for Holocaust survivors. I had not given much consideration to reparations for African Americans or Indigenous peoples. Was Jewish victimhood at the hands of Nazi Germany deserving of reparations but not African American torment or Native American suffering?

Six months later I was in Germany. We were visiting the town of Walldorf, just south of Heidelberg. Our friend Jim Klein was invited, together with family and friends, to a weekend of activities honoring the memory of his father, Kurt Klein, z”l. Kurt Klein was born in Walldorf. He left Germany in 1937. His parents hoped to follow their children to the United States. After the war began, the Kleins were deported to Vichy France. The visas they desperately sought were approved but only after they had been deported again and killed in Auschwitz.

The visit with the people of Walldorf was more interesting and uplifting than I anticipated. We attended presentations on the history of Jews living in the town. There was a discussion about confronting history. We visited the small local Jewish cemetery where generations of the Klein family were buried. There was a presentation of a musical piece crafted around a poem written by Kurt Klein.

The Germans have a lot to teach us about the methodology and meaning of reconciling with the past. Most of the people we met were not alive during World War II. A very few were alive then, like Jim’s cousin who survived the war in n Germany and remained ever since. “Germans” include tens of thousands of Jews who live in Germany and affiliate with the Jewish Community. There are estimates of two hundred thousand more Jews mainly from formerly eastern bloc countries living in Germany but not registered as Jews. Absent reconciliation, would Jews feel comfortable making Germany their home?

Remembering and reconciling is evident all over Germany. In front of houses where Jews were deported you find brass shtepplesteins, brass plates stating the names of the family members deported or murdered, and the dates and the place they were sent.

In the medieval town of Worms, on the Rhine River, there is a huge Roman Catholic cathedral. I was not much interested in visiting a Church, but Jodi beckoned us inside. Adjacent to the altar near the front, we saw large panels with historical essays, pictures, and graphs, like the panels I saw at the Reconstructing Judaism conference. The panels described the history of Jews in the Rhineland – a history marred by marauding crusaders and black plague and Nazism. The panels were next to the confessional booths. Any Catholic coming to confession would have to see the panels. If local Catholics did not have any current sins to ponder, they could always atone for the Jews who were tortured or died at the hands of their ancestors.

German reconciliation isn’t all stones and storyboards. In Berlin, we saw groups of German school children visiting the Museum of Terror and Holocaust sites. We attended a klezmer concert in the Lutheran Church of Worms. In the town of Mainz, a new synagogue of the most inspiring design was built near the center of town. The funding came from the government. The façade of the building spells out the word Kedusha in Hebrew. This New Synagogue of Mainz, in use since 2010 as a community center, was built at the location of the former main synagogue on the Hindenburgstraße of Mainz. Due to controversial discussions regarding the street name, Hindenburg being the name of the President of the Weimar Republic who invited Hitler to form a government, the location in the Hindenburgstraße was renamed Synagogenplatz (Synagogue square).

Since 1952 Germany has been paying reparations to Holocaust survivors. In September 2022, Germany agreed to a new reparations package of $1.2 B for the world’s remaining Jewish Holocaust survivors, which included $12M in emergency funds for the approximately 8,500 survivors remaining in Ukraine. Eighty percent of the many survivors in Eastern Europe live at or near the poverty level.

Gideon Taylor, president of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims said that “seventy years later, we still stand in the shadow of the six million murdered Jews. Their suffering still haunts the Jewish people and the German people.” Germany has embraced their historic responsibility. The desire for reconciliation is strongest among 30- and 40-year-old Germans who were not alive during World War Two and might not even have a parent who was alive then.

German reparations are the only instance in history of a defeated power paying reparations to individuals. Yet, initially, these payments were controversial, especially in Israel. Some survivors in Israel refused the money and said that amends could not be made. The conversation has since shifted. For many survivors the biggest concern is not financial aid but how will the world remember? Specifically, what is the moral message we want to convey?

The Germans understand the concern of teaching the world a lesson in morality. Education has now become a part of the reparations package. Some of the $1.2 Billion will be used for holocaust education.

Even here in the USA, there is a need for Holocaust education. Two-thirds of young Americans are unaware of the Holocaust and a quarter believes the Holocaust was a myth. Protecting all minority groups, ethnic groups, or religious groups will only happen if future generations are educated about the horrors of the past.

During these High Holidays, we focus on repentance, forgiveness, and atonement. We spend these days repenting our errors and seeking forgiveness AND we restore what we have damaged or taken from another person. Reparations is part of Teshuva. From the process of repentance and forgiveness, we not only change our actions, but we also transform ourselves and the world.

Teshuva is an ongoing process. Germany did not stand idly by Jews in danger in Ukraine. Germany increased reparations to include emergency aid for Ukraine’s Jewish survivors. Through a reconciliation process, Germans are demonstrating real atonement, complete with reparations.

Different than forgiveness, reconciliation allows for a relationship to be established and maintained. In fact, reconciliation can occur without forgiveness. The peaceful pathway forward is paved with humility and intentionality. In this sense, reconciliation serves as an example for future generations. The burden is on the perpetrator. The victim might never come to grips with the harm. Reconciliation demands nothing of the victim more than taking care of their own mental and spiritual health.

Reconciliation is not just between the “perpetrator and the victim”. There is a role for all of us, the next generations, as “allies”. Like young Germans in their 30s and 40s, Allies support the re-establishment of relationships. Allies reinforce the shared values among wrongdoers and those who were wronged. The allies are families, communities, and nations and their descendants.

The work of allies is not about rebuke or public shaming. The process of reconciliation operates when we recognize that something bad has occurred without presuming that the person who caused harm is themselves entirely bad. Nor are their descendants entirely bad.

The process of reconciliation is more complex in the United States. Along with the layers of oppression of Indigenous people and African Americans, many Americans today have adopted a victim mentality. Some believe that the current power structure doesn’t work for their interests and instead caters to the desires of other groups. Somehow, in an age where the country can’t seem to agree on anything, most everyone seems to agree that they are being ignored or exploited. Rich people are being overtaxed, poor people are underserved, African Americans are oppressed by institutional racism, and some whites are threatened by critical race theory. The Christian majority is in fear of becoming a minority and the Jews, well the Jews are perpetually in a state of victimhood. The danger is that victimhood becomes a roadblock to relationships. This country knows how to come together for the greater good, as we did during the second world war. But today, with the attachment to victimhood, we have lost the spirit of an American community.

Given what is taking place in our own country – the social rifts, the political divides, and a great deal of victimhood, we are in desperate need of reconciliation. No one acknowledges responsibility for any wrongs that have occurred. You might believe that your political party is best for America while the other party destroys our country. You might say that my immigrant family had nothing to do with disenfranchising indigenous people or enslaving Africans so why should I support reparations? We can hold fast to those beliefs that exculpate us from responsibility. In so doing, we may also be responsible for the unraveling of this nation.

If you attended a University like Georgetown or Harvard Law School or visited the Capitol or White House or Boston’s Faneuil Hall, you benefitted from the work of slaves. If you live almost anywhere in the United States, you likely live on land that once was home to indigenous people. Yes, your great-grandparents may have been in Ukraine when these structures went up. But if any people can appreciate the sacred legacy of a building or a land, it is the Jewish people. We still pray at the last standing wall of a Temple destroyed two thousand years ago in Jerusalem.

There is one more example of the legacy of pain unresolved. Rabbi Tirzah Firestone has written Wounds into Wisdom. She describes how the lasting effects of individual trauma have consequences for families and even entire ethnic groups. New research in neuroscience and clinical psychology demonstrates that even when they are hidden, trauma histories—from persecution and deportation to the horrors of the Holocaust—leave imprints on the minds and bodies of future generations. Rabbi Firestone writes that trauma legacies can be transformed and healed. That process includes reconciliation – seeing the humanity in each other, finding common values, and again establishing relationships.

The Jewish people practice repentance each year. We are experts in the art of reconciliation. We understand the moral imperative of reparations. Can we, you be deployed to show a way forward, here in the USA?

I am NOT advocating for or against reparations. I only mean to state that reparations may be a component of as part of the process of reconciliation. First, there must be a consensus that wrongs have been committed. America requires education and reminders. The Rockville slave quarters of Josiah Henson are now a museum facing busy Old Georgetown Road. It stands as a testament to the degradation of African Americans, unlike the Air BnB listing for the Panther Burn Cottage that proudly advertised: The property was an “1830s slave cabin” that housed enslaved people at a plantation in Greenville, Miss. removed in August.

Can we find ways to establish civil relationships among factions, parties, and communication between faith groups and minority communities? We must overcome the attachment to victimhood that mires us in disagreement and conflict. The hope of this country, the future for our children and their children, demands that we break the logjam of every person holding their victimhood precious while failing to build relationships.

Through my personal journey in 2022, I have begun to understand how reparations were part of Germany’s reconciliation with survivors of the Shoah. Given the time and complexity of the issue, reparations might not be a part of the process of reconciliation in America. However, the crucial work begins now and continues for generations, for those who were not directly responsible for slavery or eradicating indigenous peoples. The task begins with an understanding that the harm caused to others, even in generations past, is cancer that must be extracted from society. All of us benefit if we heal can heal America.

We practice repentance in our personal lives. And we have a bigger task ahead of us. Americans must engage in reconciliation for the sake of our nation.

I have undertaken to help the Scotland AME Zion church rebuild after it was left unusable from a flood in 2019. The project is not merely about a building. The project is about educating this community that many of us live on land that was owned and farmed by African Americans, who were enslaved and continued to be oppressed.

May the coming year be one in which we transcend our differences, emphasize our shared values, and establish meaningful relationships. May 5783 be the year when Americans use words to heal and not wound when the swords of victimhood are turned into the plowshares of reconciliations, when this nation shall not lift up swords against neighbors and when instead of disagreement, we learn from each other once more.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame

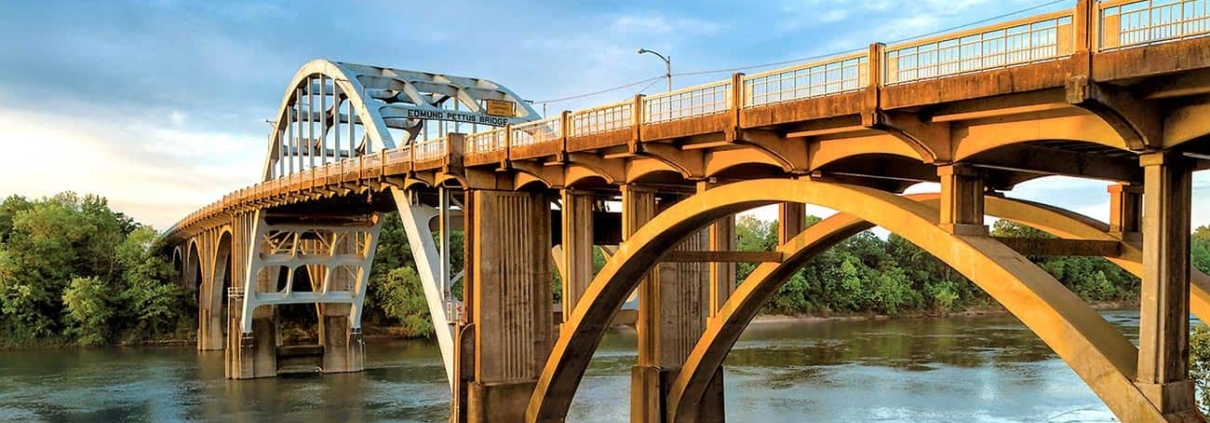

Six hundred marchers were met with horrendous violence from the police and local men deputized for this purpose. It is known as Bloody Sunday in American history. The next week, with the support of Federal Troops, the marchers made it across the bridge on a five-day, fifty-mile trek to the capital, demanding voting rights.

Six hundred marchers were met with horrendous violence from the police and local men deputized for this purpose. It is known as Bloody Sunday in American history. The next week, with the support of Federal Troops, the marchers made it across the bridge on a five-day, fifty-mile trek to the capital, demanding voting rights.

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the