Higher-archy

The civil rights movement suffered a leadership crisis during the Freedom Rides in 1961. Student-organized groups tested the segregation laws affecting interstate travel by riding buses and visiting white-only sections of bus stations. By the time they reached Montgomery, Alabama, the efforts came to an impasse. This historical episode calls to mind a populist revolt from the Torah, teaching us an enduring lesson about leadership.

In the Torah, Korach was born into a priestly family. Korach and his followers challenged Moses’ and Aaron’s leadership. “You have gone too far! The whole community is holy, every one of them, and the Lord is with them. Why then do you set yourselves above the Lord’s assembly?” Korach was correct that each member of the Hebrew community was holy. Korach was incorrect that Moses was elevated above the people. Instead, Moses was a humble leader whose obeisance to God governed his leadership style.

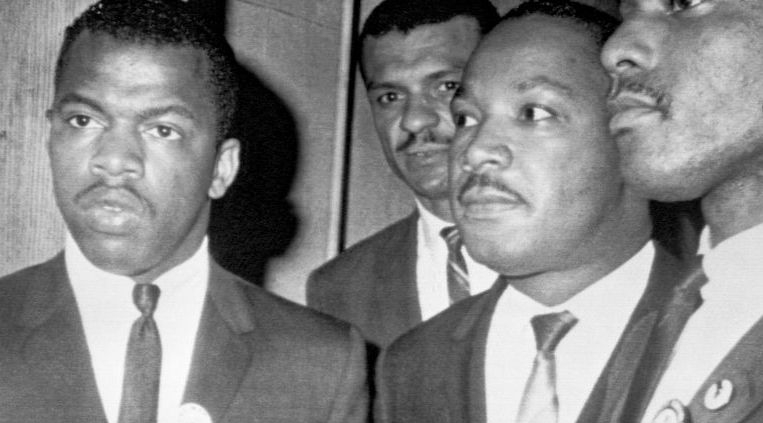

A similar confrontation occurred in Montgomery. The freedom rides began without Martin Luther King, Jr’s leadership. After a bus burning in Anniston and physical attacks in Birmingham, the riders retreated to Montgomery, where King held a pulpit. The bus companies did not wish to risk losing any more buses. The drivers feared physical assault. Yet, the students knew that the rides had to continue as press coverage of the savage attacks was vital to propelling the civil rights movement. The students were willing to risk expulsion from school and even death for this cause. They implored King to join them.

King demurred. King had already served jail time for various purported offenses, which caused him great mental stress. King’s role as the best-known civil rights leader made him the best fundraiser and spokesperson. As King declined to join them on the busses, the students griped and called him “da Lord.” They believed that King set himself above the assembly. Like Korach and his followers, I think the students were wrong.

Most Freedom Riders, like John Lewis, aligned with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The organizational ideology of SNCC was for members to share leadership. However, James Forman was SNCC’s senior leader by his maturity and organizing skills. Forman occasionally criticized King. He disliked King’s top-down leadership style and King’s melding of Christianity with Ghandian non-violence. Forman feared harm to the entire Civil Rights Movement if King was crowned with a Messiah complex.

Great leaders like Moses or King manage competing demands. Each knew there were times to lead from the front or behind. Their decision-making included an awareness that their lives might be sacrificed for a greater cause. Sometimes the threats were from within the very ranks of their people.

Korach and his followers never backed down and met a gruesome fate. Unlike Korach’s followers, the Freedom Riders met with success. They left King and returned to the busses. This time SNCC’s James Forman climbed on board. Alabama provided security for the buses to the Mississippi border.

Leadership challenges can be for holy purposes. Only with egos in check and devotion to improving the world everyone can benefit from challenges offered in a reverential fashion. Holy action is a shared endeavor that can be pursued respecting varying leadership styles.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the