Erik Larson’s new book The Demon of Unrest is a great read, just as was Devil in the White City and many others he authored. Exploring the months before Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, Larson uncovers a truth relevant to today. For a democratic nation to survive we must abide by just laws.

Southern states seceded from the union after Lincoln’s election in 1860. They had characterized him as a “black Republican” fully dedicated to the abolition of slavery. The brand was inaccurate. Lincoln was willing to uphold the laws in place at that time. He maintained that fugitive slaves be returned and the abolition of slavery deferred. The Southern perception of Lincoln was inaccurate.

Southerners, that is white Southerners, were full of pride and obsessed with chivalrous behavior. Their attachment to the Southern way of life overshadowed any attachment to the Union.

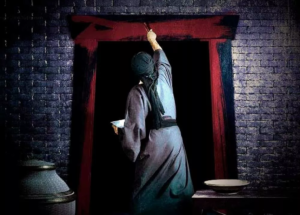

Larson’s thesis reminds me of some oft-repeated lines of the Torah about upholding the law. Parshat Behar of the Torah reminds us to obey the laws as the path to well-being. “You shall observe My laws and faithfully keep My rules, that you may live upon the land in security;” Leviticus 25:18. As the South was not quite the Promised Land, the principles of obedience to the laws and fidelity to the Union did not resonate well enough.

Of course, Larson was reflecting on the current state of the Union. The issues confronting us today are many. Be it immigrants, abortion, or prejudices, many Americans now cling to a bellicose former President who pridefully endorses carnage over fidelity. As our electoral processes are under attack, the systems by which our democracy is upheld are undermined.

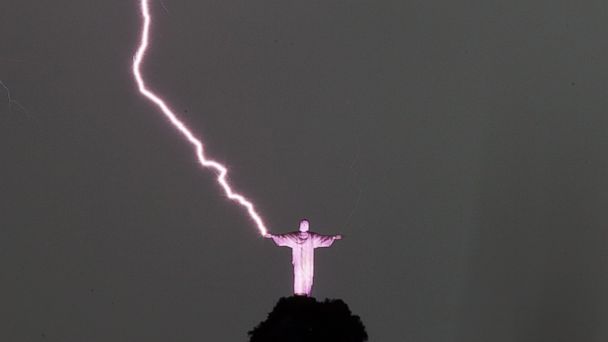

I believe there is a spiritual aspect to our nation’s current distress. A spiritual person understands submission of the ego to the Divine or a greater cause. A result of religious practice is to learn both obedience and fulfillment. The faithful observance of law, albeit just laws, is a neglected virtue.

Our nation has endured civil war, caused largely by arrogance, defiance, and disregard for law. Those same problems exist today, and I pray that they don’t result in yet another civil war.

Rabbi Evan J. Krame

Within two days of her demand, the parliament banned semi-automatic weapons. Describing the victims, most of whom were immigrants to New Zealand, Ardern said: “They are us. The person who has perpetuated this violence against us is not. They have no place in New Zealand.” Ardern later remarked that “the characteristics we should necessarily deploy in troubled times are defined by the kind of humanity” we should always bring to leadership.

Within two days of her demand, the parliament banned semi-automatic weapons. Describing the victims, most of whom were immigrants to New Zealand, Ardern said: “They are us. The person who has perpetuated this violence against us is not. They have no place in New Zealand.” Ardern later remarked that “the characteristics we should necessarily deploy in troubled times are defined by the kind of humanity” we should always bring to leadership.

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the

Evan J. Krame was ordained as a rabbi by the